August 01, 2025 | Karl’s Korner

August 01, 2025 | Karl’s KornerMidway's Commissioning

On Oct. 27, 1943, a new keel was laid inside the basin of Newport News Shipbuilding’s Shipway 11 within a fortnight of the launching of the Essex-class aircraft carrier USS Franklin (CV-13).

This new carrier in the making was going to be a giant, but she still lacked a name, merely the hull number CVB-41. Construction proceeded briskly, thanks to welding and the fabrication of modular sub-assemblies. By January 1944, the foundations and watertight confines of the machinery spaces were established, and one year later, the armored hangar deck took shape. Meanwhile, consideration was turned to which name to assign to the new carrier.

Naming conventions of the time favored applying classical U.S. Navy ship names or legacy battles to fast carriers, and since the field of such available monikers was fast-shrinking, the idea of assigning the names from carrier key battles of the still-being-fought World War II for this strikingly new flattop seemed sensible. However, escort carriers had taken on a fresh tradition of being named after new battles in World War II, and the name “Midway” had been bestowed upon an escort carrier (CVE-63) six months earlier.

Despite a superstition against changing ship names, the crew of the CVE-63 was informed their vessel’s name was now the USS St. Lo while they were already deployed to the Pacific and preparing for the Leyte invasion in the Philippines. Just 15 days later, the St. Lo was sunk in the first kamikaze attack of the war.

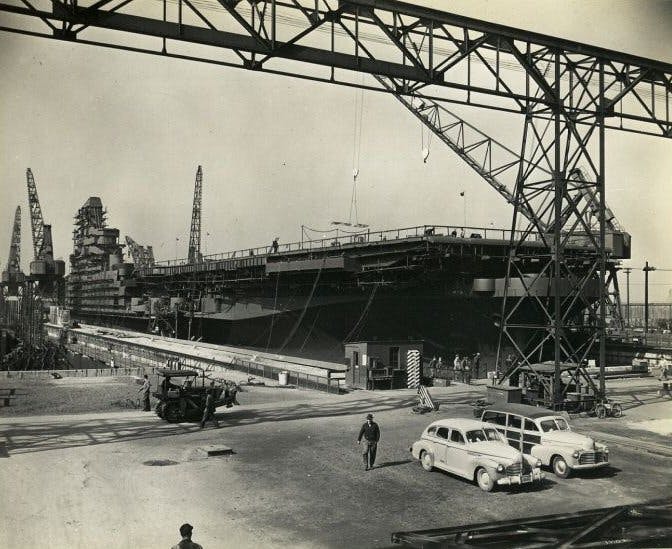

Back in Virginia, the three-shift, seven-day-a-week progress on CVB-41 culminated on March 20, 1945, with the launching ceremony for the new USS Midway. As per the custom of Newport News Shipbuilding, the “North Side Force” (shipbuilders) hoisted a broom aloft to signal that they were finished with their work and it was time for the “South Side Force” (outfitters) to take over when the ship arrived at the outfitting basin nearby.

Pleasant weather greeted the attendees as the bow towered over a special barge that floated into place to support the christening party. The ship’s sponsor was Barbara Cox Ripley, daughter of James M. Cox, a candidate for president in 1920, whose running mate was Franklin D. Roosevelt. Also present on the ceremonial barge was Lt. George Gay, the sole survivor of Torpedo Squadron 8 (VT-8) from the Battle of Midway in 1942.

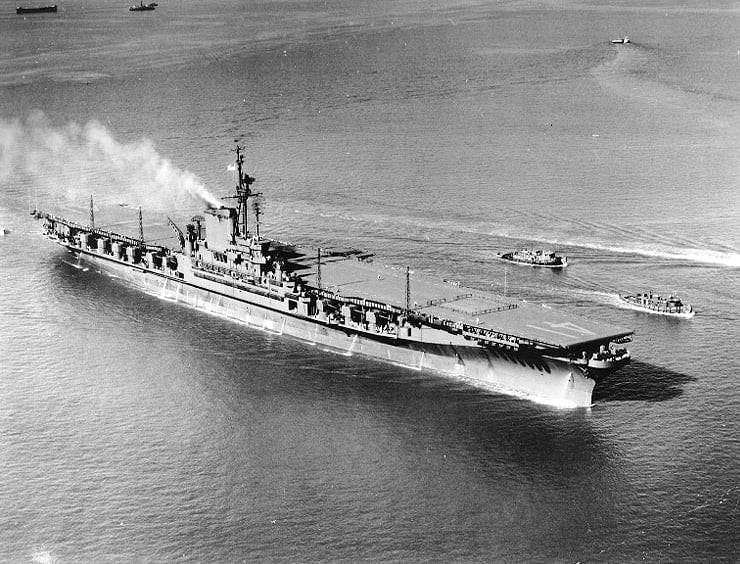

Three ceremonial ribbons connecting the hull to the dock were cut, symbolizing the release from the land, and at 9:43 a.m., Mrs. Ripley smashed a bottle of champagne against the hull. However, a freshening breeze that morning meant the tight-fitting Midway had to wait until the afternoon to begin the delicate process of being hauled out of the graving dock into the stream. At just after 5 p.m., Midway began moving for the first time. An hour later, tug boats carefully nestled the Navy’s newest carrier alongside the outfitting pier.

Though Allied armies were rolling into Germany, fighting still raged on Iwo Jima and the assault on Okinawa was in the offing. There was every expectation that World War II would continue well into 1946. Combat damage resulting from the kamikaze onslaught in the western Pacific revealed a marked disparity between the wooden decked U. S. carriers and the armored British flattops. American carriers struck by the Kamikaze suicide air attacks required extensive repairs to return to service, while the British Navy’s Illustrious-class carriers stood up well. The new armored flight-deck on Midway could very well undergo such a trial in the expected invasion of Japan.

To get the newest carrier and her large air group up to shape quickly, the Navy turned to two combat veterans. Capt. Joseph Bolger had taken the carrier USS Intrepid (CV-11) back into combat after battle repairs in 1944 and fought through campaigns in the western Pacific until Kamikaze damage forced the Intrepid’s return to California in early 1945. Orders to the new Midway awaited him. Before winter had ended, men were already assembling in Boston and attending various training schools in New England while a nucleus crew of veterans joined Captain Bolger at Norfolk.

In keeping with the notion that Midway was a big step forward in carrier aviation, her air group sported a new designation, CVBG-74. Forming at the naval auxiliary air facility at Otis Field near Cape Cod, CVBG-74 comprised ninety-six F4U Corsairs and forty-six SB2C Helldiver bombers. This massive unit came under the leadership of colorful Cmdr. John “Tommy” Blackburn, who had led the celebrated Fighter Squadron 17 (VF-17). Known as the “Jolly Rogers,” the seasoned pilots of Fighting 17 had already fought in intensive air combat in the South Pacific.

As the fitting out process at Newport News proceeded swiftly, Germany went down to defeat and America’s armed services braced for a pair of bloody landings on Japan: Kyushu in November, and Honshu in March 1946. Meanwhile, a drastic alternative to ending the war took shape in the New Mexico desert, and in Washington, D.C. The prospect of unleashing atomic weaponry to avert a costly assault became undeniable to the new Truman administration, and after an ultimatum and two atomic bombings, Japan accepted terms for surrender on Aug. 14, 1945.

While the Allied world reveled in the victory, men still received orders to report for new construction in Norfolk to man Midway. More than 2,100 officers and sailors comprised the ship’s company, while another 1,300 joined with air group. They discovered a vast yet cramped ship when all the battle protection features were reckoned with. Tall sailors were obliged to stoop below decks, and the stacks of bunks squeezed within the lowered deck clearances made shifting while abed problematic. More than two thousand compartments also meant that staying within well-defined regions was a must to avoid getting lost. Engineers grunted as they traced piping systems across the largest engineering plant in the fleet, while the supply department rushed to account for the inundation of equipage, parts, and paperwork to stock Midway.

Finally, on Sept. 10, 1945, Midway cast off from the outfitting pier and cruised across Hampton Roads to the Norfolk Navy Yard for her commissioning later that afternoon. A cooling trend broke a late summer hot spell as the crew mustered by divisions on the large, open flight deck. Rows of sailors in their whites, Marines in khaki, with some chief petty officers dappling the scene in wartime gray uniforms, and officers in dress whites with swords stood before a delegation of dignitaries including the president of Newport News Shipbuilding, Homer Ferguson; the ship’s sponsor, Mrs. Ripley; Navy Under Secretary Artemis Gates; and Rear Adm. Walden Ainsworth, veteran of the South Pacific and now Commandant of the 5th Naval District; as well as Capt. Bolger.

In ritual fashion, Adm. Ainsworth accepted Midway from Mr. Ferguson and presented her to Capt. Bolger to assume command. Upon reading his orders, Bolger directed his executive officer, Cmdr. Rudolph Bauer, to “Set the watch.” With the first watch section “set,” speeches and a benediction followed before the guests and crew were dismissed and invited to attend receptions at various “messes indicated on the guest card.” The USS Midway’s near half-century career had just begun.

Launch em’… until next time,

Karl

Your Adventure Starts Now

Your email is the key to information that will open up all your possibilities for exploring the mighty Midway!